When Jung was around twelve years old, a fellow school student knocked him over. As the young Jung fell, he hit his head such that he nearly lost consciousness.

It was after this point that Jung experienced fainting spells every time he was supposed to go to school. For more than six months, Jung stayed away from school. He spent his time in nature and isolation. He read and played in the woods. He drew pictures of battles and castles. And he drew pages and pages of caricatures.

Here’s a quote from Memories, Dreams, Reflections about the period:

“But I was growing more and more away from the world, and had all the while faint pangs of conscience. I frittered away my time with loafing, collecting, reading and playing. But I did not feel any happier for it. I had the obscure feeling that I was fleeing from myself.”

Jung’s parents consulted doctor after doctor about the situation. One doctor thought that he had epilepsy. Another sent him away on holiday with relatives. But other than that, there was nothing that the doctors could do to cure the young Jung.

One day, a few months after the incident, Jung overheard his father talking to a friend. His father expressed concern that Jung would never be able to support himself or find work.

Here’s a quote:

“I heard the visitor saying to my father, ‘And how is your son?’ ‘Ah, that’s a sad business’, my father replied. ‘The doctors no longer know what is wrong with him. They think it may be epilepsy. It would be dreadful if he were incurable. I have lost what little I had, and what will become of the boy if he cannot earn his own living?’”

This speaks to how dire the situation was for Jung’s father. But for Jung, something changed in that moment. He realised that he needed to pull himself out of the destructive pattern of avoidance. He describes that moment as a collision with reality.

He went into his father’s study and started doing schoolwork. He started with Latin grammar. After about ten minutes, the slightest fainting spell came on. He almost fell off the chair—but he managed to persist through the attack.

After a while, he started feeling better. He told himself, “Devil take it. I’m not going to faint.”

The second attack came after fifteen minutes. He continued working. In fact, the second fainting spell made him more determined to see it through. Fuelled by determination, he worked longer. The third attack came after an hour. Again, Jung persisted. He worked for another hour. He kept working until he felt that the fainting spells had completely subsided.

At this point, he felt better than he had in months. In his own words, he says, “The whole bag of tricks was over and done with! That was when I learned what a neurosis is.” Jung had cured his own neurosis—a remarkable feat for a twelve-year-old. After that he had the courage to return to school.

This is a testament to how self-aware Jung was even at a young age. The shoving incident had left him traumatised. He confronted the fear complex head-on when he went into his father’s study and started working on his Latin grammar.

It’s also interesting that Jung takes complete responsibility for the incident. He doesn’t harbour any negative feelings towards the boy who knocked him over. He sees himself as the culprit because he allowed himself the opportunity of avoidance.

Here’s what he says in the memoir:

“Gradually the recollection of how it all came about returned to me, and I saw clearly that I myself had arranged this whole disgraceful situation. That was why I had never been seriously angry with the schoolmate who pushed me over. I knew he had been put up to it, so to speak, and that the whole affair was a diabolical plot on my part. I knew too this was never going to happen to me again. I had a feeling of rage against myself, and at the same time was ashamed of myself.”

What happened after this point is just as interesting. Jung became unusually diligent. He would, from that point on, wake up early in the morning—five or even earlier—to study for a few hours before school.

This shows enormous self-discipline, especially for a boy of twelve. And as he explains in the memoir, this was not done for the sake of appearances. He did this for his own benefit.

“Nevertheless it induced in me a studied punctiliousness and an unusual diligence. Those days saw the beginnings of my conscientiousness, practised not for the sake of appearances, so that I would amount to something, but for my own sake. Regularly I would get up at five o’clock in order to study and sometimes I worked from three in the morning till seven before going to school.”

For me, this tale speaks to what we can achieve when we face our own fears. Indeed, there’s a treasure trove of wisdom in this story.

For one thing, Jung is very clear that he deceived himself. There was no one to blame but himself. Just that little nugget alone contains enormous wisdom. Talking about the fainting spells, he says at one point, “I forgot completely how all this came about.” This is often what happens when we ignore our own conscience. We become veiled as to what’s really going on. There is no way to return to the initial clarity of thought if we don’t confront the fear head on.

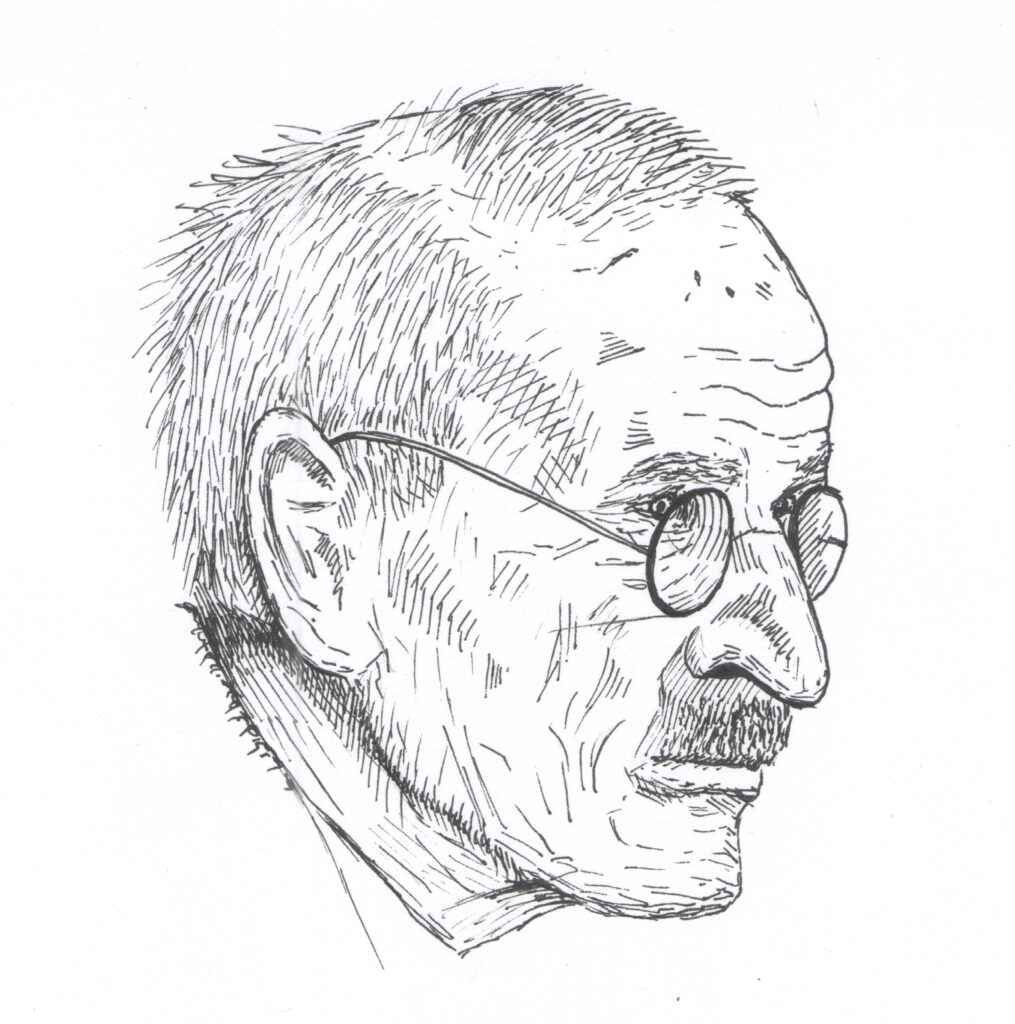

It took the words of Jung’s father to snap him out of the state of unconscious avoidance. And the result of this was far-reaching. Jung became an exceptionally well-read, well-spoken young man. Later still, he became one of the greatest thinkers of all time. He probed deeply into the human psyche. He left behind an enormous body of work and influenced countless psychoanalysts and thinkers who came after him.

All of this happened because he was willing to face his fears. This wasn’t easy for him. From reading Memories, Dreams, Reflections, it is clear that Jung was sensitive to his surroundings and the judgements and ideas of others. His unusual sensitivity also left him feeling isolated for much of his life. But he walked the inner path bravely. That is something we should all aspire to.